General information about Oman

Introduction

Oman’s economy is expected to contract in 2020 due to the oil price slide and the COVID-19 public health response. An increase in gas output and infrastructure spending plans will help growth recover over 2021-22. Fiscal and external deficits will remain under strain due to low oil and gas prices. Rigid recurrent spending will keep public debt high, estimated to exceed 70% of GDP in 2020 and beyond. Real GDP growth is estimated to have decelerated to 0.5% in 2019, down from a recovery of 1.8% in 2018. This is largely driven by 1% (y/y) decline in oil production, capped by the since-lapsed OPEC+ production deal. The non-oil economy is estimated to have been subdued due to the slowdown in industrial activities and services sector. Inflationary pressures are estimated to remain muted at 0.1% in 2019, reflecting weak domestic demand and tame food and housing prices.

Low oil prices and the spread of COVID-19 are the key challenges that Oman will need to navigate in the short-run. With oil prices in the mid-$30s in 2020 and constrained oil demand, growth is expected to contract by 3.5%. Forty five percent of Omani exports (or 21.7% of GDP), mostly oil, go to China, the highest Chinese exposure among GCC. Low oil prices will create challenges to the implementation of supportive public spending for the country with already high deficits, more limited buffers and an elevated debt level. As such, the fiscal deficit is expected to markedly widen to over 17% of GDP in 2020, before starting to slightly narrow down over 2021-2022, assuming more favorable oil prices.

ogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Key downside risks are reflected in further erosion of the fiscal balance, through far lower oil prices, exposure to China, and economic disruption to tourism due to COVID-19. Mitigation would be demonstrated by implementation of substantial fiscal measures to curtail the government deficits, a new push on privatization, and prioritizing capital projects. With its accumulated external debt, Oman will need a rapid normalization of emerging market funding conditions to finance the continued deterioration of the country’s fiscal and external accounts. Significant new gas production in 2021 along with diversifying the economy in sectors such as manufacturing, tourism, fishing and aquaculture will support the growth momentum and lessen the risks. At the same time, enabling Petroleum Development Oman (PDO) to maintain or increase its oil and gas production has sizable investment needs. (The World Bank, 2020).

Aquaculture is one of the fastest growing food production systems in the world. It currently contributes 50 per cent of global fish production. This proportion will increase to 62 per cent by 2030, according to reports issued by the World Bank.

The aquaculture sector in Oman is on the cusp of boom, with major fish farms either in the planning or advanced stage of development, which is in line to increase revenues from the sector to RO222mn by 2023.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries said that the sultanate’s production of aquaculture in 2019 had amounted to 1,054 tonnes, an increase of 133 per cent compared to 2018, with a total value of RO2mn.

The ministry, according to the outputs of the fish resources laboratories ‘Tanfidh’, seeks to increase the contribution of the aquaculture sector to RO222mn by 2023, through several aquaculture projects, the most important of which are shrimp and abalone, seabream, cobia and Jack fish, in addition to algae.

The production of Indian white shrimp reached 352 tonnes in 2013. But the production fluctuated for years to decrease to 86 tonnes in 2016. In June 2018, the first commercial production of European Seabream started in a fish farm in the Wilayat of Quriyat that uses floating cages. Its production was 350 tonnes by the end of 2018. By the end of 2019, the production increased to 862 tonnes.

On the other hand, integrated aquaculture witnessed a growth in the production of tilapia as production increased from 20 tonnes in 2015 to 192 tonnes in 2019.

The ministry hopes that the aquaculture sector will be one of the main pillars in developing and improving the utilization of fish resources in the sultanate and that this sector will be able to compete and meet the consumers’ needs for high-quality marine products in a manner compatible with the environment (Muscat Daily, 2020).

In this book at first, I have introduced general vision about aquaculture opportunities and potential of Sultanate of Oman and history of starting aquaculture projects in Oman then I have tried classified different information and activities about aquaculture industry, a different system of aquaculture such as aquaponic, integrated farming, cage culture in Oman. Also, I have illustrated commercial species of aquatic organisms in government and private sectors, in addition, educational and research centers have been introduced in the end of this book I have brought all held events and all Aquaculturist in Oman.

I hope this book will be useful for those interested in aquaculture activities and domestic and foreign investors, students and researchers in the agricultural and aquaculture industry.

Oman location

The Sultanate of Oman is found in the South-Eastern corner of the Arabian Peninsula and is located between latitudes 16°40΄ and 26°20΄ North and longitudes 51°50΄ and 59°40΄ East. Considered as the third largest country in the Arabian Peninsula, it has a total land area of 309,500 sq km. It covers vast gravel desert plains and mountain ranges and a long coastline of 3,165 km. Bordering on its north side is the Strait of Hormuz and the United Arab Emirates, on the northwest by Saudi Arabia while at the southwest by the Republic of Yemen. Three seas surround the country: the Arabian Gulf, the Sea of Oman, and the Arabian Sea .The current population is 4.8 million people. The greater part of the country has a dry climate except for the south which is subtropical. Dhofar Region has most of the moisture through seasonal rainfall, the south-west monsoon brings in fog or rain in the area. Thus, the larger part of the country’s biodiversity is being supported in this region.

Oman is part of the Gulf Regions’ varied landscapes and seascapes. The country has the typical salt flats or salt plains (sabkha), lagoons or saline creeks (khwars), oases and stretches of sand and gravel plains, which are dominated by mountain regions. The Hajar mountain ranges run from Musandam through most of northern Oman along the Sea of Oman. These mountains vary in width from 30 to 70 km and are mostly steep

and barren formations of igneous and sedimentary rocks. They rise to almost 3,000 masl at Jabel Shams, the highest point in the country. The terrain is crossed by riverbeds or dry river valleys (wadis) which are formed by surging water during the rainy season but most remain dry until the next flooding. Off the coasts are several islands and islets, the largest of which is Masirah Island on the east.

A long stretch of desert is a typical feature of Oman. The almost endless Rub’ Al Khali (Empty Quarter) covers the southwest of the country which traverses the neighboring Saudi Arabia and the UAE while a vast Wahiba Sands is nestled in the northeast. In great contrast is the greener southern Dhofar region, which is humid-tropical in appearance since it receives relatively high rainfall than the rest of the country.

Climate:

Oman is situated along the edges of moisture-rich air masses: one coming from the Mediterranean and the other from the Indian Ocean. Along the coasts is hot and humid while in the interior is hotter but drier. Hot summer months are from May to September and the cool winter months start in November until March. In Muscat, the daily average maximum temperature is 41 ºC in late June and July but the minimum at around 16.5 ºC in the colder months (Hawley, 2005).

Rainfall appears irregular with December and January are months of heaviest rainfall. Mean annual rainfall is less than 50 mm in the interior regions and around 100 mm in coastal areas. Mean monthly relative humidity is highest in coastal areas ranging from 50-90%. Much drier air is felt in the interior areas at 1-2%. Wind is under the influence of the equatorial convergence zone. In summer, this system reaches southern Oman and brings monsoon conditions to the Dhofar mountains. In winter, the system moves to south of the equator. Wind direction is generally moving from the north while in summer it is from the south. Cyclones occasionally occur in the country creating disastrous flash floods. The Super-Cyclone Gonu, which entered the Sea of Oman from 5-7 June 2007, was Oman’s worst natural disaster and the largest Cyclone on record to strike the Arabian

Peninsula. Highest winds were over 260 km/h in the Arabian Sea and the storm severely damaged coastal areas including 1,000s of sq m of reef damaged near Muscat.

Biodiversity

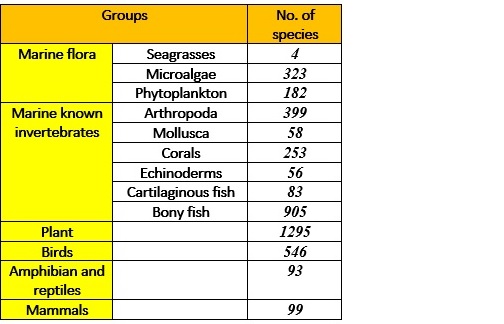

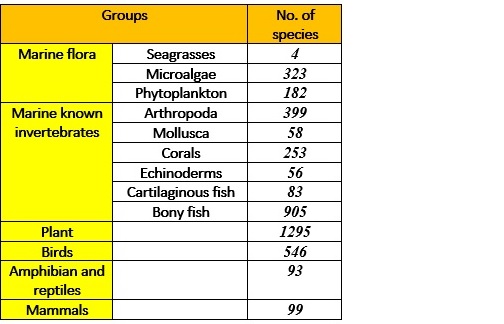

Distinguished as a unique biogeographic region, northern Oman’s biodiversity has strong affinity with its neighboring Iran and Pakistan species. At the far south is its increasing influence of African species. A number of relict species is prevalent in a number of habitats in the country. The vegetation of Oman is influenced by two major plant groups: the Saharo-Sindian (Arabian) groups in the west and central Oman and the Somalia-Masai (African) groups in the south (Ghazanfar and Fisher, 1998). Table 1 shows an updated tally of biodiversity found in Oman indicating conservation status of each group.

Wetlands, Islands and Marine Biodiversity

Wadis, khwars, sabkhas and mangrove forests encompass the country’s wetlands. Seasonal water flows or wadis are one of the most common and important landscape elements in Oman draining rainwater from wide catchment areas and high mountains. Terraces along wadi banks are intensively farmed. Vegetation along wadis include Tamarix, Saccharum sp., Nerium mascatense, Ficus cordata and Acacia nilotica. Alluvial plains support growth of Acacia, Ziziphus, Moringa and Ficus salicifolia. Extensive sand dunes are associated to the coastal areas and are important protector of beaches. The dunes and their associated grasses and shrubs trap marine sands which help prevent both the erosion of beaches and the covering of inland areas by wind-blown sand.

Khwars are productive and valuable fish-breeding and nursery areas supporting dense masses of Enteromorpha, mullet fishes and the edible crab Scylla serrata. Fig. 2 shows a typical lagoon in the Dhofar region.

Coastal plains and sabkha vegetation are dominated by mosaic-like communities of halophytes, drought-decidious thorn woodlands and open xeromorphic shrublands and grasslands. There are four coastal vegetation communities recognized (Patzelt and Al Farsi, 2000): 1) Limonium stocksii-Zygophylum quatarense community in northern Oman where the coasts are mainly sandy and interspersed with rocky limestone, 2) Limonium

Wetlands, Islands and Marine Biodiversity

Wadis, khwars, sabkhas and mangrove forests encompass the country’s wetlands. Seasonal water flows or wadis are one of the most common and important landscape elements in Oman draining rainwater from wide catchment areas and high mountains. Terraces along wadi banks are intensively farmed. Vegetation along wadis include Tamarix, Saccharum sp., Nerium mascatense, Ficus cordata and Acacia nilotica. Alluvial plains support growth of Acacia, Ziziphus, Moringa and Ficus salicifolia. Extensive sand dunes are associated to the coastal areas and are important protector of beaches. The dunes and their associated grasses and shrubs trap marine sands which help prevent both the erosion of beaches and the covering of inland areas by wind-blown sand.

Khwars are productive and valuable fish-breeding and nursery areas supporting dense masses of Enteromorpha, mullet fishes and the edible crab Scylla serrata. Fig. 2 shows a typical lagoon in the Dhofar region.

Coastal plains and sabkha vegetation are dominated by mosaic-like communities of halophytes, drought-decidious thorn woodlands and open xeromorphic shrublands and grasslands. There are four coastal vegetation communities recognized (Patzelt and Al Farsi, 2000): 1) Limonium stocksii-Zygophylum quatarense community in northern Oman where the coasts are mainly sandy and interspersed with rocky limestone, 2) Limonium

Wetlands, Islands and Marine Biodiversity

Wadis, khwars, sabkhas and mangrove forests encompass the country’s wetlands. Seasonal water flows or wadis are one of the most common and important landscape elements in Oman draining rainwater from wide catchment areas and high mountains. Terraces along wadi banks are intensively farmed. Vegetation along wadis include Tamarix, Saccharum sp., Nerium mascatense, Ficus cordata and Acacia nilotica. Alluvial plains support growth of Acacia, Ziziphus, Moringa and Ficus salicifolia. Extensive sand dunes are associated to the coastal areas and are important protector of beaches. The dunes and their associated grasses and shrubs trap marine sands which help prevent both the erosion of beaches and the covering of inland areas by wind-blown sand.

Khwars are productive and valuable fish-breeding and nursery areas supporting dense masses of Enteromorpha, mullet fishes and the edible crab Scylla serrata. Fig. 2 shows a typical lagoon in the Dhofar region.

Coastal plains and sabkha vegetation are dominated by mosaic-like communities of halophytes, drought-decidious thorn woodlands and open xeromorphic shrublands and grasslands. There are four coastal vegetation communities recognized (Patzelt and Al Farsi, 2000): 1) Limonium stocksii-Zygophylum quatarense community in northern Oman where the coasts are mainly sandy and interspersed with rocky limestone, 2) Limonium

Wetlands, Islands and Marine Biodiversity

Wadis, khwars, sabkhas and mangrove forests encompass the country’s wetlands. Seasonal water flows or wadis are one of the most common and important landscape elements in Oman draining rainwater from wide catchment areas and high mountains. Terraces along wadi banks are intensively farmed. Vegetation along wadis include Tamarix, Saccharum sp., Nerium mascatense, Ficus cordata and Acacia nilotica. Alluvial plains support growth of Acacia, Ziziphus, Moringa and Ficus salicifolia. Extensive sand dunes are associated to the coastal areas and are important protector of beaches. The dunes and their associated grasses and shrubs trap marine sands which help prevent both the erosion of beaches and the covering of inland areas by wind-blown sand.

Khwars are productive and valuable fish-breeding and nursery areas supporting dense masses of Enteromorpha, mullet fishes and the edible crab Scylla serrata. Fig. 2 shows a typical lagoon in the Dhofar region.

Coastal plains and sabkha vegetation are dominated by mosaic-like communities of halophytes, drought-decidious thorn woodlands and open xeromorphic shrublands and grasslands. There are four coastal vegetation communities recognized (Patzelt and Al Farsi, 2000): 1) Limonium stocksii-Zygophylum quatarense community in northern Oman where the coasts are mainly sandy and interspersed with rocky limestone, 2) Limonium

- stocksii-Suaeda aegyptica community characteristic or rocky shores with narrow beach areas and a wide spray zone, 3) Atriplex-Sueda community along offshore islands, flat sandy beaches and coastal sabkhas, 4) coastal lagoons with Sporobolus virginicus, Sporobolus iocladus and Paspalum vaginatum as bordering species and Phragmites australis and Typha spp forming bordering reeds.

- Fishery-related damage causing coral reef breakage; caused by tangled gill nets and boat anchors

- coastal destruction

- litter

- recreational activities

- oil pollution

- discharges from desalination plant

- enriched water discharges from sea farms

- Drying of sardines and discard of fish offal, old nets, oil drums, rusted freezers and other litter on fish landing beaches diminishes their value for recreation.

- People lacking support of fisheries resource management due to ignorance or inadequate knowledge and information.

- Gross wastage of fishes together with the capture of undersize and berried crayfish is depleting fishery resources. , polluting beaches, and potentially threatening some species, notably crayfish, sharks and groupers with local extermination..

- Coastal archeological sites are being lost to coastal development, damaged by vehicle traffic and road works, looted by amateurs or degraded by litter before they are studied.

- Human predation of breeding seabirds and their eggs has resulted in local extermination of breeding colonies

- Mangroves , reeds and rushes are endangered by development pressure,overgrazing, infilling, pollution and dumping of garbage

- Intermittent illegal discharges of oil at sea off the coast contaminate the beaches with oil and tarballs, destroy their recreational value and threaten the breeding seabird colonies

- Escalating sand mining activities or the demand for sand by new development schemes could lead to disappearance of smaller beaches.

- Careless fishing practices are damaging corals thereby reducing aesthetic value of reefs for recreation, and their productive value for fisheries, through entanglement of nets, ropes and anchors

- Enriched waste water from inland containment lagoons enters the khawrs and solid wastes are dumped in the khawrs, mangroves and wadis, on the beach and into the sea

- Coral reefs in much of Mussandam are being devastated by the Crown-of-thorns Starfish (Acanthaster planci) and temperature-induced bleaching of the corals

- Breeding population of turtles are threatened by collision with the high speed boats of Iranian traders and heavy oil and flotsam pollution of their nesting beaches

- Gunnery target practice by Royal Navy of Oman causes disturbance to seabirds

- Tourism village, fisheries and other development projects may create the need for new or upgraded roads and improved access to the seashore could stimulate beach erosion, damage coastal environments and reduce their value for recreation, wildlife and fisheries, or lead to further loss of beaches.

- 18 species of isopods with nine endemic species and one endemic genus, Omanodillo (Crustacea: Oniscidea; Gardner, 2000)

- 40 species and subspecies of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpions; Gardner, 2000)

- 221 sp of insects plus eight species of gastropods (DGNC, 2009)

- 58 species of sandy beach macrofauna (polychaetes, oligochaetes, crustaceans and mollusks: McLachlan, et al., 1998)

- 182 species diatoms, dictyocha, dinoflagellates and cyanobacteria (Al Azri, 2009)